What a real business failure taught me about choosing the wrong Machine Learning problem

I spent six months teaching myself machine learning. Watched dozens of YouTube tutorials. Completed two online Machine Learning (ML) courses. I have built practice models on Kaggle datasets. I felt ready.

Then I tried applying regression vs classification concepts to a real business problem at Lia’s Flowers, a small flower shop I was helping optimize. The predictions looked beautiful on screen. In reality, they were useless. We threw away flowers, disappointed customers, and wasted money.

That failure taught me more about machine learning for beginners than any course ever could.

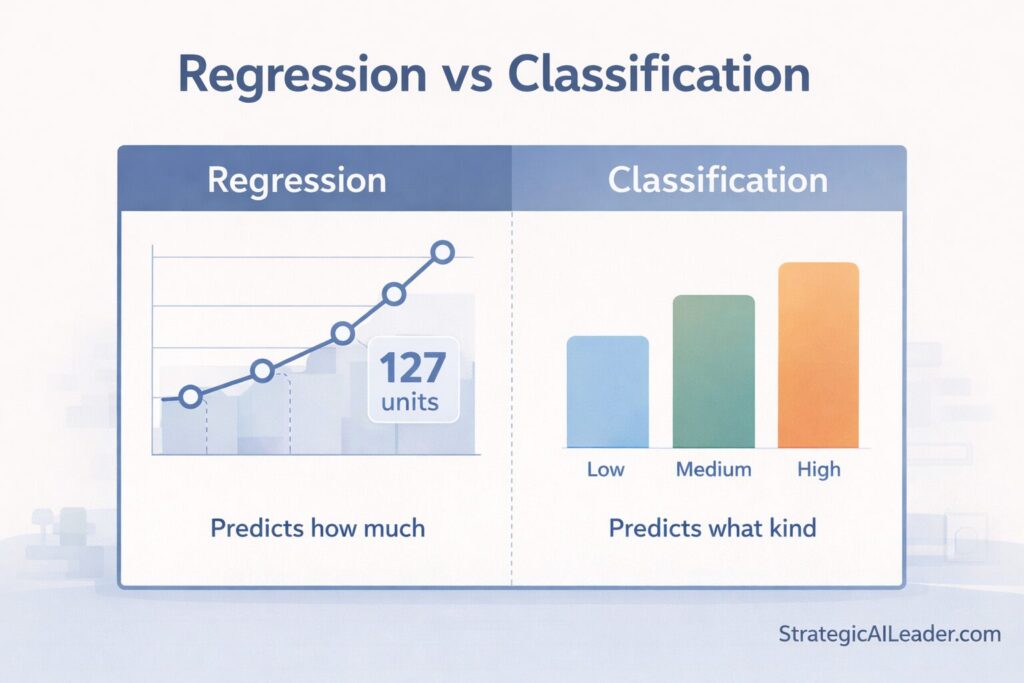

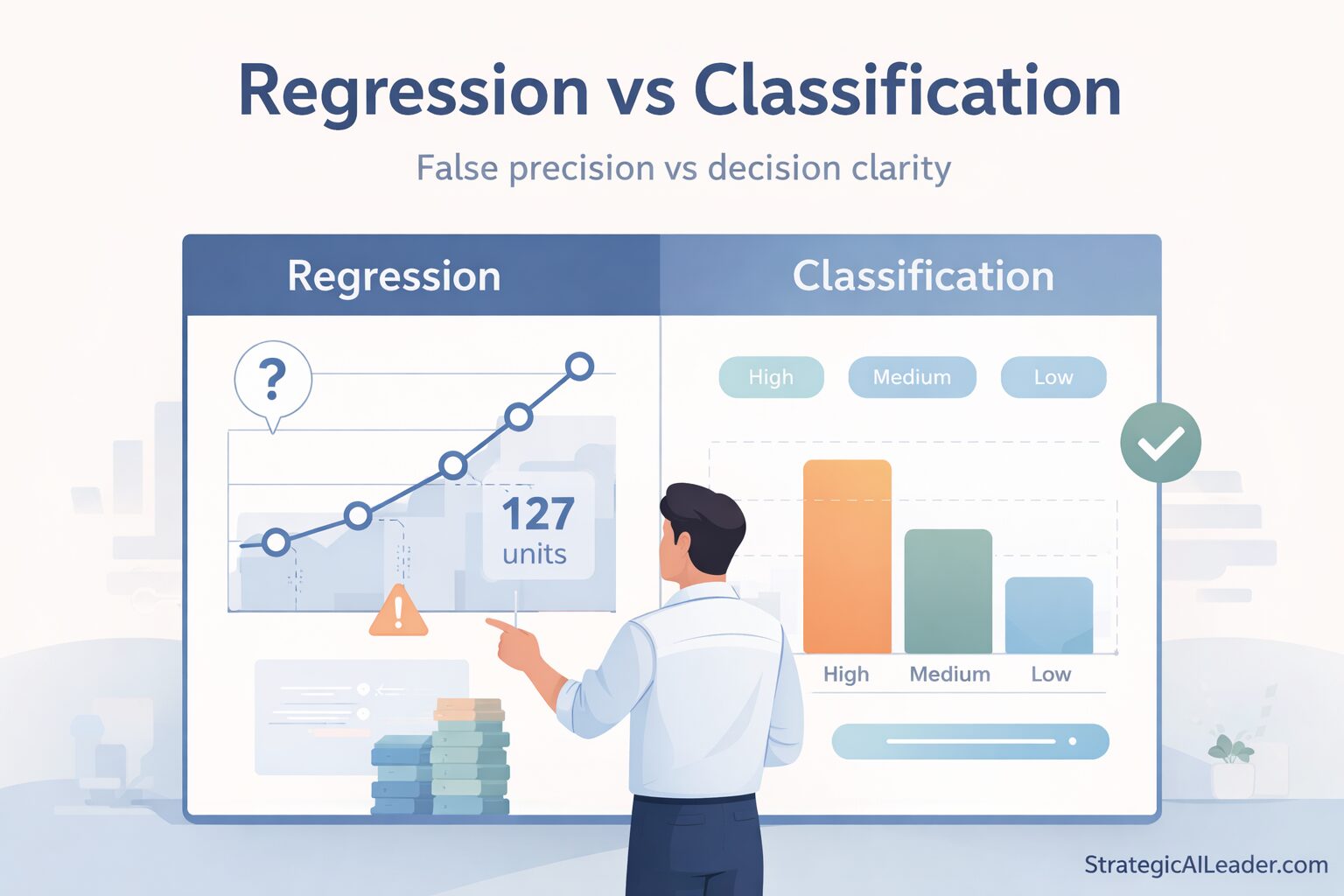

TL;DR: Regression predicts “how much” (127 roses). Classification predicts “what type” (high/medium/low demand day). I used regression for a flower shop, but it didn’t work because I needed classification. The business required decision categories, not false precision.

The Problem Seemed Simple Enough

Lia’s Flowers faced the same challenge every perishable goods business faces. Order too many roses, and they die in the cooler. Order too few, and you turn away Valentine’s Day customers who never come back.

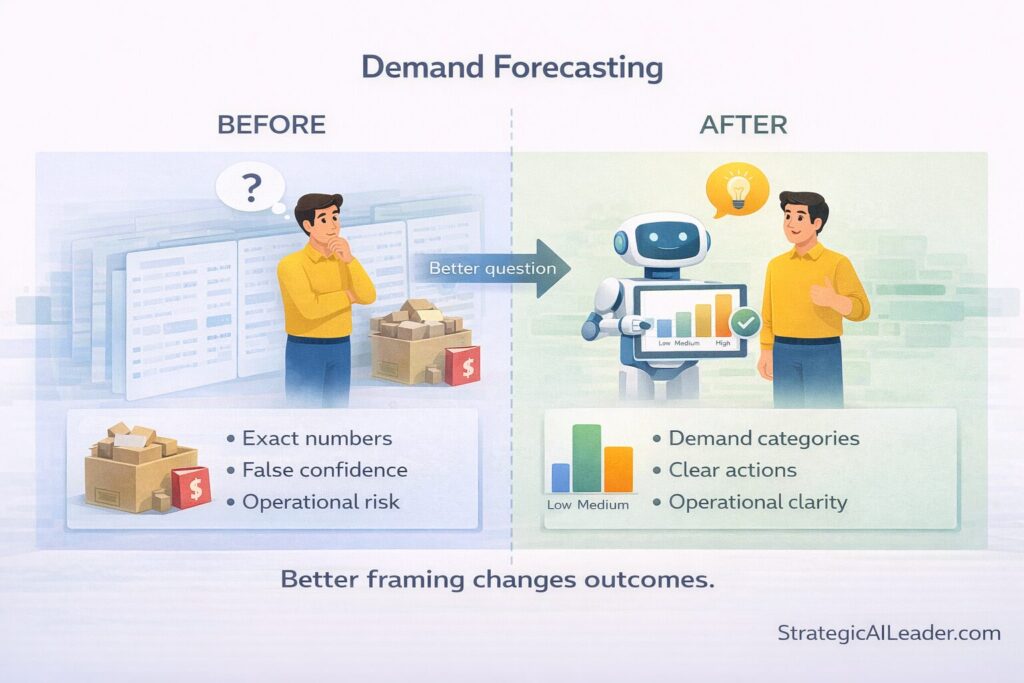

Demand forecasting was the perfect first machine learning project. I had months of sales data. Weather information. Local event calendars. Holiday schedules. The tutorials made it look straightforward. Plug in the data, train the model, and get predictions.

I chose regression because the courses said it predicts continuous values. I needed to predict stem counts. Seemed like an obvious fit.

When Regression Predictions Fail: A Demand Forecasting Example

My model predicted we’d sell 127 roses on a particular Saturday. We ordered 130 to be safe. Felt scientific. Data-driven. Professional.

We sold 43.

I remember Lia looking at the cooler full of dying roses. She didn’t say anything. She didn’t have to. I’d just proven that six months of courses couldn’t beat twelve years of running a shop. The model was sophisticated. Her instinct was accurate. I felt like an idiot, luckly she is my wife and is supportive of my journey.

We composted $380 of roses that first week. I later documented the complete breakdown of that failure, including the numbers, decisions, and what finally worked, in a detailed Lia’s Flowers demand forecasting case study.

The following week, the model predicted 89 stems of mixed tulips. We ordered 90. We sold 156 and ran out by noon.

The predictions weren’t wildly off on average. Over a month, the total error was only about 15%. But that average hid a brutal truth. Being slightly wrong every single day is worse than being right most days and very wrong occasionally.

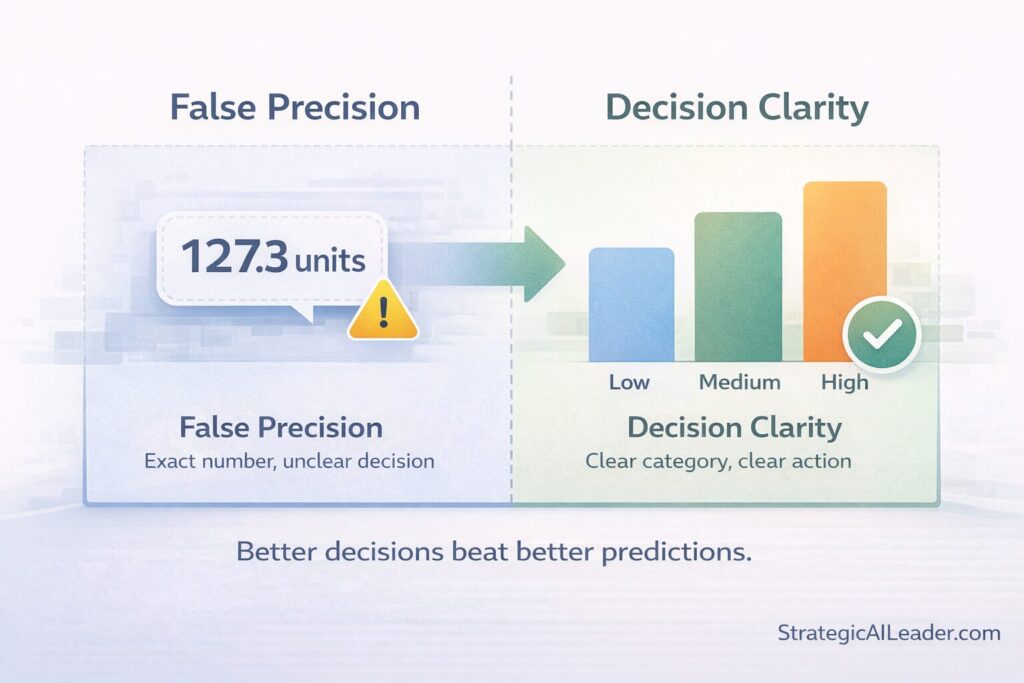

The business couldn’t operate on “close enough.” Kitchen tables don’t need 127.3 roses. They need roses, or they don’t. Wedding orders either happen or they don’t. You can’t deliver 0.7 of an arrangement.

Regression vs Classification: What I Wish I’d Understood First

Here’s what finally clicked after the failure. Machine learning has different tools for different question types. Regression vs classification isn’t about complexity. It’s about what you’re actually trying to predict.

Both regression and classification are types of supervised learning.

Regression answers: How much?

Regression predicts numbers on a continuous scale. Temperature. Price. Distance. Quantity. When you need a specific measurement, you use regression.

For Lia’s Flowers, regression tried to predict exactly 127 roses. Or 89.4 tulips. Precise numbers that felt sophisticated but didn’t match how the business actually made decisions.

Classification answers: What kind?

Classification predicts categories. High or low. Yes or no. Red, blue, or green. Category A, B, or C.

What I should have asked: Will tomorrow be a high-demand day, a medium-demand day, or a low-demand day? That’s classification. That’s how Lia actually made ordering decisions before I showed up with my fancy models.

I Was Solving the Wrong Problem Type

The fundamental mistake wasn’t picking the wrong algorithm. I framed the entire problem incorrectly.

Lia didn’t need to know she’d sell exactly 127 roses. She needed to know if Saturday would be busy, regular, or slow. She’d been running the shop for twelve years. She knew what “busy” meant. She knew how much to order for each category.

My regression model tried to be more precise than necessary. Precision sounds good. In practice, precision on the wrong question is just expensive noise.

If I’d started with classification, I would have asked the model: Based on weather, day of the week, and recent patterns, is tomorrow’s demand high, medium, or low?

Then Lia could apply her expertise. High demand? Order the full range plus extras of popular items. Low demand? Scale back to basics and specialty requests only.

How to Choose a Machine Learning Model Without the Jargon

Every machine learning course covers the basics of supervised learning. They explain algorithms. Loss functions. Hyperparameters. All useful eventually.

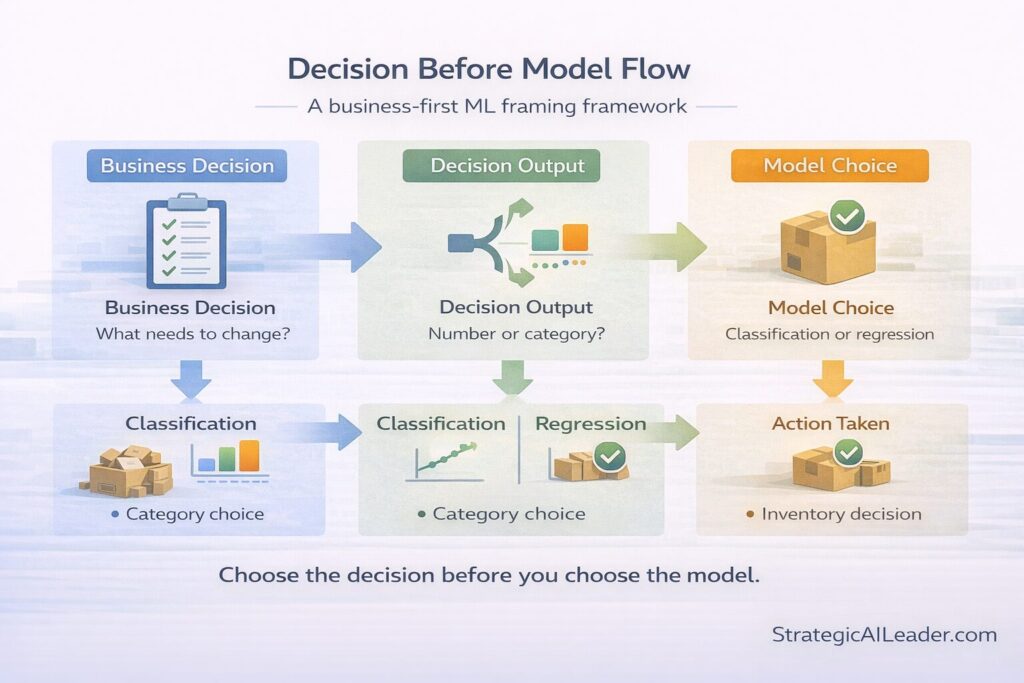

But they bury the most important lesson. Model selection is secondary to decision framing.

Before touching any model, write down the decision you’re trying to make. Use plain English. Avoid the word “predict” if you can.

For Lia’s Flowers, the decision was: How much inventory should I order tomorrow?

That sounds like a regression problem. It’s not. Break it down further.

The real decision: Should I order at the high, medium, or low level?

Now you have a classification problem. Three categories. Clear boundaries. Actionable outputs.

Reframing the question changed everything. Classification gave Lia decision-worthy information. Regression gave her false precision she couldn’t use.

What Changed After I Stopped Trying to Be Clever

I rebuilt the system around classification. The model predicted demand categories, not exact numbers. High, medium, low.

We added a simple rule. On high-demand days, if the model was confident, order 20% above normal. On low-demand days, order 30% below normal. On medium days, stick to baseline.

Waste dropped from $2,400 per month to $1,440 per month in the first month. Stockouts went from 8 per week to 3 per week. Lia stopped second-guessing the system because the decisions made sense to her.

The model wasn’t more accurate in absolute terms. It was useful. That’s what matters for inventory forecasting for small business operations.

The best model isn’t the most accurate one. It’s the one that improves the decision you were already trying to make.

Richard Naimy

Why Failing Is Actually the Machine Learning Curriculum

Courses teach you syntax and theory. Kaggle competitions teach you optimization tricks. But neither teaches you how to translate a messy business problem into the right ML question.

You learn that by being wrong. Expensively wrong. Publicly wrong.

I learned more from debugging my Lia’s Flowers failure than I did from completing three courses. The courses taught me that regression exists. The failure taught me when not to use it.

Pattern after pattern repeated as I kept learning. Every real project taught me something no video could. Overfitting vs underfitting makes sense in theory. In practice, you know it by watching your model memorize training data and bomb on next Tuesday.

If you’re learning machine learning independently, treat your first three projects as guaranteed failures. Budget for them. Plan for them. The failure is the point.

According to McKinsey research on AI implementation, approximately 70% of machine learning projects fail due to poor problem framing, not technical execution. The data scientists get the math right. The business leaders frame the question wrong.

Your Machine Learning Project Checklist

Before starting any ML project, especially if you’re working through machine learning for beginners material, run through checklist items like these:

Start with the business decision. Write it in one sentence without ML jargon. What decision do you need to make?

Use classification before chasing precision. Can you turn the problem into categories? High vs low? Yes vs no? Do that first.

Expect your first model to be wrong. Plan for failure. Make the stakes small. Test on decisions that won’t sink the business.

Measure mistakes in business terms. Don’t obsess over accuracy percentages. Ask: What happens when the prediction is wrong? How much does that cost?

Treat failure as a curriculum, not a setback. Every wrong prediction teaches you something about your data, your problem, or your framing. Log it. Learn from it. Iterate.

Common Questions About Regression vs Classification

What’s the simplest way to know if I need regression or classification?

Ask yourself: Am I predicting a number or a category? If you need “how much” or “how many,” use regression. If you need “which type” or “yes/no,” use classification.

For demand forecasting, most people jump to regression because they want quantities. But often what you really need is a tier system. High-demand week, medium-demand week, low-demand week. That’s classification with a clear business meaning.

Can you use both regression and classification on the same problem?

Absolutely. For Lia’s Flowers, I could have used classification to predict demand level, then regression within each category to fine-tune quantities. Start with classification to frame the decision, then add regression for precision if needed.

Many successful inventory forecasting systems for small businesses work exactly like that. Classify the demand state first. Apply quantity logic second. Building that kind of staged decision system prevents the false precision trap I fell into.

What’s more accurate: regression or classification?

Wrong question. Accuracy depends on your data and problem framing, not the model type. A well-framed classification problem beats a poorly-framed regression problem every time.

Accuracy metrics can lie. My regression model had 85% accuracy on a test set. In operations, it was worthless because the 15% errors came at the worst possible times. A classification with 75% accuracy would have performed better in reality, as mistakes would have been smaller and more manageable.

The Real Learning Starts After the Course Ends

I have three ML certifications and read every AI strategy framework I could find. None of them prepared me for the Lia’s Flowers disaster. The certifications taught me tools. The disaster taught me judgment.

You can’t learn judgment from videos. You know it by making real decisions with real consequences. You understand it by wasting real money on dire predictions. You realize it by explaining to a frustrated shop owner why your “scientifically optimized” system just cost her a weekend of sales.

That education is uncomfortable. It’s also irreplaceable.

Research from Harvard Business Review on integrating AI shows that AI technology is only about 10% of successful implementation. The other 90% lies in properly integrating it into specific business context with the right combination of data, experimentation, and talent. The best data scientists in the world can’t help you if they’re solving the wrong problem.

If you are learning machine learning as a beginner, do not fixate on the math. You can use AI to help you work through formulas and mechanics as you learn. The harder skill is framing the problem correctly. You only develop that skill by getting it wrong first and adjusting. Focus on decisions. Let AI handle the math while you build judgment.

Regression vs classification isn’t a technical distinction. It’s a thinking distinction. It’s learning to ask the right question before you chase the correct answer.

And you only learn that by getting it wrong.

Key Takeaways: What Actually Matters When Learning Machine Learning

Problem framing beats model selection. Spend three hours defining your business decision before you spend three minutes picking an algorithm. Please write it down. Make someone explain it back to you. If they’re confused, your framing is wrong.

Start with categories, not precision. Classification is easier to validate, explain, and trust. Build confidence with simple categories before chasing regression precision.

Measure success in dollars, not accuracy scores. An 85% accurate model that loses $2,400 per month is worse than a 75% precise model that saves $960 per month. Business metrics trump technical metrics every single time.

Budget for three failures minimum. Your first ML project will teach you what doesn’t work. Your second will teach you why. Your third might actually solve something. Plan accordingly.

Real learning happens in production, not in courses. Kaggle competitions are practice. Business applications are the game. You can’t learn to play basketball by reading the rulebook.

The Lia’s Flowers project cost me about $8,000 in wasted inventory and lost sales over two months. The best education I ever bought. Couldn’t have learned it any other way.

Final Reflection

Machine learning looks intimidating from the outside. Algorithms, mathematics, data pipelines. But the real skill isn’t technical. It’s knowing what question to ask.

Start small. Choose a real problem. Frame it with precision. Expect mistakes. Measure where you missed. Refine the framing. Commit to lifelong learning and keep leaning in.

That’s the curriculum. Everything else is just syntax.

Regression vs Classification FAQs

What is the difference between regression and classification in machine learning?

Regression predicts a number. Classification predicts a category. If you need to know how many units you will sell, that is regression. If you need to know whether demand will be high, medium, or low, that is a classification. The key difference is not math. The key difference is the type of decision you need to make.

Are regression and classification both supervised learning?

Yes. Both regression and classification are types of supervised learning. They learn from labeled historical data. The difference lies in the output. Regression learns to predict numeric values. Classification learns to predict categories or labels.

Why did regression fail for demand forecasting at Lia’s Flowers?

Regression failed because the business did not need exact quantities first. The shop needed to know demand level categories before deciding quantities. Predicting precise numbers created false confidence and led to waste and stockouts. Classification aligned better with how teams actually make inventory decisions.

When should I use classification instead of regression?

Use classification when decisions happen in tiers or buckets. Examples include high vs low demand, yes vs no outcomes, risk levels, or priority categories. If people already think in categories, start with classification before chasing precision.

Can regression and classification be used together?

Yes. Many effective systems use both. Classification frames the decision by identifying the demand state. Regression refines the decision by estimating quantities within each category. This staged approach avoids premature precision.

What is the biggest mistake beginners make with regression vs classification?

The biggest mistake is choosing a model before defining the decision. Beginners often jump to regression because they want numbers. In practice, many business problems require categorization before teams can act. Wrong framing beats wrong math every time.

Why does model accuracy not equal business success?

Accuracy measures how often a model predicts correctly. Business success depends on the cost of being wrong. A high-accuracy model can still lose money if errors occur at the worst times. The best model improves decisions, not metrics.

How should beginners choose a machine learning model?

Start by writing the decision in plain language. Ask what action will change based on the output. Decide whether the output needs to be a number or a category. Only then choose between regression and classification.

How much data do I need to start a machine learning project?

You need enough data to support the decision, not to impress a model. Start small. Use historical data you already trust. If you cannot explain the data to a business owner, do not model it yet.

Stay Connected

I share new leadership frameworks and case studies every week. Subscribe to my newsletter below or follow me on LinkedIn and Substack to stay ahead and put structured decision-making into practice.

Related Articles

AI Task Analysis: How Top Performers Cut Workflow Time 40%

The AI Trap That Makes AI Change Risk Invisible

The Truth About AI Native Content Systems and Visibility

Understanding Model Context Protocol | A Practical Guide for AI Teams

AI Visibility Systems: The New Era of Search Control

Agentic Browsers Explained: The Truth About AI Search

Claude Skills vs MCP: Inside the New AI Capability Layer

The GEO Operating System: A New Model for AI Visibility

Hybrid AI Agent Systems: The Leadership Edge in Automation

The Ultimate AI Agent Strategy for Leaders Who Want ROI

About the Author

I’m Richard Naimy, an operator and product leader with over 20 years of experience growing platforms like Realtor.com and MyEListing.com. I work with founders and operating teams to solve complex problems at the intersection of product, marketing, AI, systems, and scale. I write to share real-world lessons from inside fast-moving organizations, offering practical strategies that help ambitious leaders build smarter and lead with confidence.

I write about:

- AI + MarTech Automation

- AI Strategy

- COO Ops & Systems

- Growth Strategy (B2B & B2C)

- Infographic

- Leadership & Team Building

- My Case Studies

- Personal Journey

- Revenue Operations (RevOps)

- Sales Strategy

- SEO & Digital Marketing

- Strategic Thinking

Want 1:1 strategic support?

Connect with me on LinkedIn

Read my playbooks on Substack

Leave a Reply